Urinary System Infections Treatment

Non-antibiotic Prophylaxis for UTIs

Urinary tract infections are common but also annoying health problems. They affect, in particular, 50% of women, while the proportion of men is much smaller during their lifetime.

The human body is equipped with many defensive mechanisms to maintain the urinary tract of microbes. Among them, they are urine with their acidic pH, the bay with its normal flora but also its specific antibodies, the urethra and the bladder.

Pathogenic microorganisms enter the urethra and compete with the normal flora that exists there. Urine flow drives the free germs but also the urethral cells, to which microbes have been attached and excreted in the urine.

Furthermore, the production of immunoglobulins and cytokines, create barrier conditions for pathogens. The urinary bladder has its own defense mechanisms and prevents adhesion of microbes either with the epithelium layer or with proteins that adhere to E. coli fibrils, preventing adhesion, either by its mechanical contractions or by the flow of urine, which prevents stasis and colonization of the bladder.

The causes of UTIs can vary

In women, due to their anatomy, the small length of the urethra contributes to perineal infections. Furthermore, a pregnancy with the hormonal and anatomical changes it causes creates the conditions for urinary tract infections. Sexual activity often creates conditions for urinary tract infections. The menopause stage, with changes in the mucosal epithelium, is a factor that can contribute to urinary tract infections.

Women who have had such a urinary tract infection are likely to relapse from time to time

Some urinary tract infections are just painful (sometimes very painful) and annoying. Some people are more sensitive than others. However, some urinary tract infections - especially if they are chronic, recurrent or not treated directly and correctly - can be quite dangerous.

Under such conditions, germs can rise to the kidneys (rising infection), where the infection can lead to serious damage, even in renal insufficiency.

Urinary tract infections are mostly microbial. The most common causative agent is gram-negative germs. Although 90% of urinary tract infections are caused by E. Coli, the remaining 10% is caused by bacteria known as Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, Neisseria gonorrhea and others.

Unlike E. coli, this class of germs is transmitted through sexual contact and rarely causes more serious infections in both the bladder and the kidneys.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) accounts for 80% of urinary tract infections, while other gram-negative germs, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis and Enterobacter aerogenes, contribute somewhat less to the incidence of urinary tract infections.

Gram positive grains represent less infections of the urinary tract than gram-negative microbes. Staphylococcus saprophyticus (responsible for 10-15% of urinary tract infections in women aged 20-25 years), enterococci and staphylococcus aureus (most common in people with urinary tract stones or who have a history of urinary tract infection) are among the involved microorganisms catheter).

Nearly one-third of women with dysuria and other symptoms of urinary tract infections have "sterile urine" - with or without pimples. In the case of "urinary sterilization" and esophagus, etiological factors are often sexual transmission, with neisseria gonorrhea or chlamydia trachomatis. Non-microbial etiological agents include myoplasm (ureaplasma urealyticum or mycoplasma hominis), and candida albicans (especially in diabetics or catheterized patients).

Medical treatment of urinary tract infections involves the use of antibiotics because the majority of urinary tract infections are microbial.

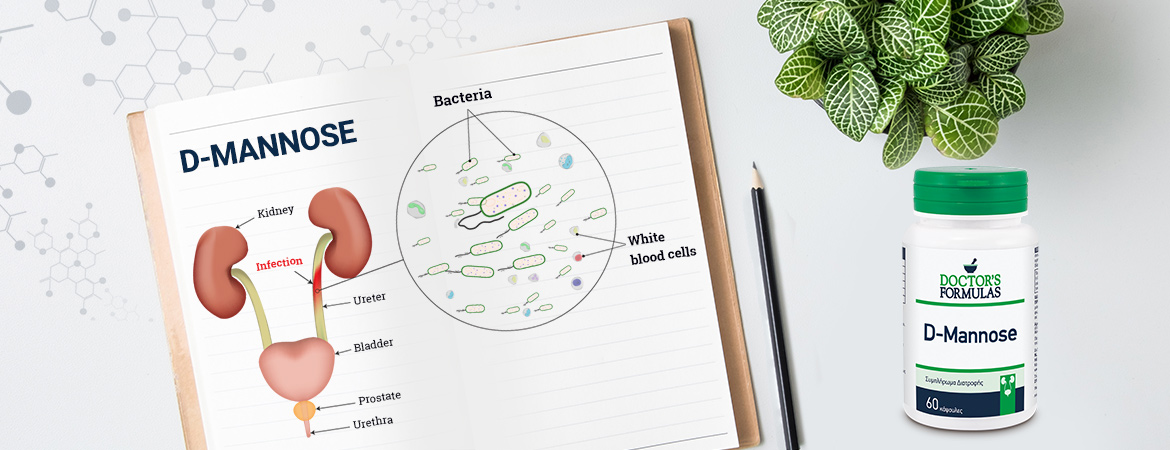

- coli, the most common pathogen associated with urinary tract infections, has been extensively studied to determine its mode of action. One parameter that is essential for its infectious effect is its ability to adhere to the epithelial cells of the urinary system.

Adherence of microbes to uroepithelial cells is the first and important step in the onset of infection

Both for E. coli and Proteus, the fimbriae, the protein capillary surface components, mediate the binding of microbes to specific epithelial cell receptors. At the edge of each fimbria is a glycoprotein (a combination of carbohydrates and protein) called lectin that is programmed to bind to the first molecule of mannose it meets.

What is D-Mannose?

D-mannose is a simple sugar that has a particular contribution to metabolism through its role in the glycosylation of certain proteins. D-mannose is rapidly absorbed and reaches about 30 minutes in the peripheral organs and is then secreted from the urinary system. It cannot be converted into glycogen; therefore, it is not stored in the body. Furthermore, long-term use of D-mannose, at concentrations up to 20%, showed no adverse effect on human metabolism

Mechanism of Action

Its mechanism of action is expressed by inhibiting E. coli attachment to uroepithelial cells via the FimH surface protein. By the direct binding of FimH to D-mannose associated with a carrier protein, which is responsible for receptor specificity. In vitro studies have identified specific lectin for mannose on the surface of adherent E. coli strains. There are other in vitro studies that have clarified the attachment mechanism.

D-mannose holds a dominant position in the bladder cell receptors in E. coli uropathogen

The first adhesion step involves the mannose-sensitive binding of FimH to the bladder epithelium. The bladder wall is coated with various mannose glycosylated proteins, such as the Tamm-Horsfall (THP) protein that directly interferes with the adhesion of microbes to the mucosa. The Tamm-Horsfall (THP) protein can bind to E. coli with a specific bond which can be inhibited by exogenous D-mannose.

By inhibiting the adhesion of microbes to the urinary tract epithelium, D-mannose mimics the function of the epithelial barrier of the urinary tract

The process of microbial adhesion to the cell surface is a critical factor in the occurrence of most infections. This is because certain lectins in the microbial wall are capable of binding molecules, such as D-mannose and L-fucose, that are distributed to the human cell surface.

The mannose molecules act as "receptors," inviting E. coli's fringes to adhere. E. coli fimbriae are surface organisms that mediate binding to structures containing D-mannose.

Bibliography

-

Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine.16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2005.

-

Foxrnan B. Recurring urinary tract infection: incidence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1990; 80:331-3.

-

NICKEL JC. Practical management of recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women. Rev Urol 2005; 7:11-17.

-

GUPTA K, STAMM WE. Pathogenesis and management of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. World J Urol 1999; 17: 415-420.

-

ALTON G, HASILIK M, NIEHEUS R, FANA F, FREEZE HH. Direct manipulation of mannose for mammalian glycoprotein biosynthesis. Glycobiology 2001; 8: 285-295.

-

SHARON N. Carbohydrates as future anti-adhesion drugs for infectious diseases Biochim Biophys Ac- ta 2006; 1760: 527-537.

-

PAK J, PU Y, ZHANG ZT, HASTY DL, WU XR. Tamm- Horsfall protein binds to type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli and prevents coli form binding to uroplakin Ia and Ib receptors. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 9924-9930.

-

KLEIN T, ABGOTTSPON D, WITTWER M, RABBANI S, HEROLD J, JIANG X, KLEEB S, LUTHI C, SCHARENBERG M, BEZENCON J, GULBER E, PANG L, SMIESKO M, CUTTING B, SCHWARDT O, ERNST B. FimH antagonists for the oral treatment of urinary tract infections: from de- sign and synthesis to in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Med Chem 2010; 53: 8627-8641.

-

Fowler J E, Jr., Stamey TA. Studies of introital colonization in women with recurrent urinary infections. Vll. The role of bacterial adherence. J Urol. 1977; 117:472-6.

-

Ofek 1, Goldhar J, Esltdat Y, Sharon N. The importance of mannose specific adhesins (lectins) in infections caused by Escherichia coli. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1982; 33:61-7.

-

Herman RH. Mannose metabolism. 1. Am J Chn Nutr. 1971:24: -188-98.

-

Ofek I, Beachey EH. Mannose binding and epithelial cell adherence of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 1978; 22:247-254.

-

Hung CS, Bouckaert J, Hung D, et al. Structural basis of tropism of Escherichia coli to the bladder during urinary tract infection. Mol Microbiol 2002; 44:903-915.

-

Firon N, Ashkenazi S, Mirelman D, et al. Aromatic alpha-glycosides of mannose are powerful inhibitors of the adherence of type1 fimbriated Escherichia coli to yeast and intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 1987; 55:472-476.

-

Schaeffer AJ, Chmiel JS, Duncan JL, Falkowski WS. Mannose-sensitive adherence of Escherichia coli to epithelial cells from women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Urol 1984; 131:906-910.

-

Wellens A, Garofalo C, Nguyen H, et al. Intervening with urinary tract infections using anti-adhesives based on the crystal structure of the FimH- oligomannose-3 complex. PLoS ONE 2008;3: e2040.